Aléf (الف). The story starts offline, but it doesn’t become a story until it’s digitally captured, spread. The story is, a year ago, in July 2024, a short video surfaced online. Short: 1 minute, 16 seconds. Filmed vertically in Karaj—a city not long ago considered a more affordable suburb of Iran’s capital, Tehran, which in 2010 itself became the capital of a new Iranian province, Alborz, and today boasts a population of 1.6 million, making it Iran’s fourth largest city—the video depicted teenage girls and young women refusing Iran’s compulsory veiling laws while wielding chains in annual Ashura procession.

Bé (ب). The story goes viral as the video raises different sets of questions for different audiences. For Iranians, the sight of women, of their uncovered hair glistening in the sun as they march the streets beating chains against their shoulders, an act traditionally reserved for boys, men, commands attention. For non-Iranians, the sight of chains against bodies, an unfamiliar commemorative ritual, intrigues. Summoned by authorities for questioning, the young women have already posed their questions on the streets: Who are you to restrict how I show up and partake in religious rituals? Why does the state arbitrate sociality, religiosity, visibility?

1. Zan.

Figure 3. Locks of hair collected together to spell out zan (woman) at the Art University of Tehran, 26 October 2022.

Pé (پ). The story starts offline, but it doesn’t become a story until it’s digitally captured and spread, after Jina (Mahsa) Amini was killed. On 16 September 2022, the 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman succumbed to the injuries she sustained while in state custody, picked off the streets of Tehran while on a family trip by the guidance patrol (gasht-e ershad) that functions through ambiguity, arresting Iranian women for so-called “inappropriate” covering and “violation” of arbitrary dress codes. For a majority of women who walked the streets looking no different from the next, it was impossible to know when their turn would unluckily come.

Figure 4. Jina Amini in a coma in Kasra Hospital after being brutalized by Iran’s Guidance Patrol.

Té (ت). The story was first reported on by journalist Niloofar Hamedi via tweet. Something her spouse reminded everyone of in an Instagram story on 30 October, over a month after Hamedi’s own arrest on 22 September, the same day her Twitter account was suspended. Along with a picture of Jina’s parents at Kasra Hospital, she wrote: Her grandmother was singing a melody in Kurdish and her father who had just arrived from Hashtgerd, was saying please save my daughter. Woe is me, woe is us. There was nothing we could do. But black garments have been, are our flag.”

Figure 5. Screenshot of an Instagram story sharing the 29 October 2022 post by Mohamad Hosein Ajorloo of his wife Niloofar Hamedi’s initial tweet that would land her in prison, with the added hashtag, #niloofarhamedi.

Sé (ث). The story was just beginning. Journalist Elahe Mohammadi’s reporting on Jina’s funeral in Saqqez, Kordistan, would land them in jail too. In their 18 September article, “A Whole Country of Grief,” Mohammadi wrote about the over a thousand townspeople that showed up to bury the daughter they considered theirs, sharing the Kurdish slogan they chanted while carrying Jina’s casket through the cemetery: “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî.” Zan, Zendegi, Azadi. Woman*, Life, Freedom (WLF). Two years later, the expression “enghelabe zan, zendegi, azadi” (the WLF Revolution) easily rolled off the tongues of young women in conversation. What happened in between?

Figure 6. Feature photo of a flyer announcing Mahsa (Jina) Amini’s passing with information on the memorial services to be held in her honor, which accompanied Elahe Mohammadi’s article on Mahsa (Jina) Amini’s funeral that resulted in their arrest.

Jeem (ج). The story is now the story of Zan in Iran, which doesn’t start or end here, but imagining zan without jin, without jina, is today impossible. Finding its etymology in the Middle Persian Pahlavi word, jin (ژن), the word zan (زن) shares roots with the Greek word γυνή (gynē), which transliterated to Persian, is pronounced jina (ژینا). Whoever wrote on her tombstone “Dear Jina / you will not die / your name will become a symbol,” seemingly knew something of the past and future, of words and languages and roots and revolutions.

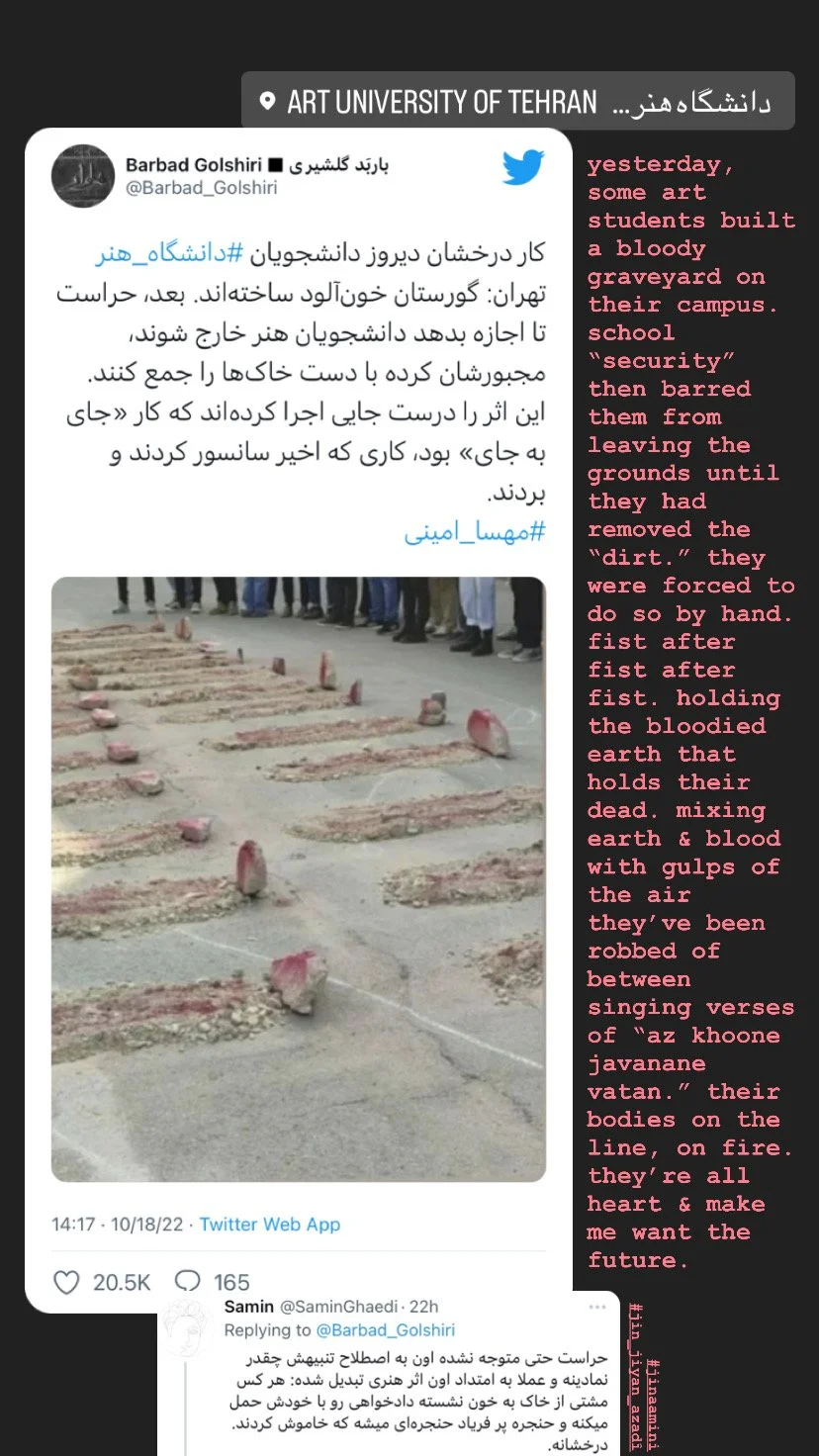

Ché (چ). The story was lived intimately by young women who were university students, commuting across their cities and towns daily and subjected to the policing eyes of the guidance patrol at strategic stops along the way. No surprise, they were among the first to organize: be it from breaking down the gender segregation of their school cafeterias by occupying space or staging protests—particularly by the students at the Iran University of Art*, who pulled from and added to Iran’s rich repertoire of protest art. Every one of them risked expulsion to “stand up,” to say: no.

*Better known as Art University of Tehran, referencing where it’s based.

Figure 8. Screenshot of an Instagram story by the author sharing a tweet by Iranian artist Barbad Golshiri noting the poignancy of an impromptu installation by students at the Art University of Tehran.

Hé (ح). The story of their “no”s rang out through original songs, like “In the name of the girls of the land of sun,” “Promise” (“I wrote you this letter from the dust of cold alleyways with my blood so that smiles may grow on lips […] promise to the blood of my comrades, to the tears of mothers”), and “The Song of Equality” (“I’ll grow sprouts on my bodily wound […] we’ll build another world of equality, in empathy and sisterhood”). And through new lyrics to global protest tunes as old as Quilapayún’s “El Pueblo Unido Jamás Será Vencido.”

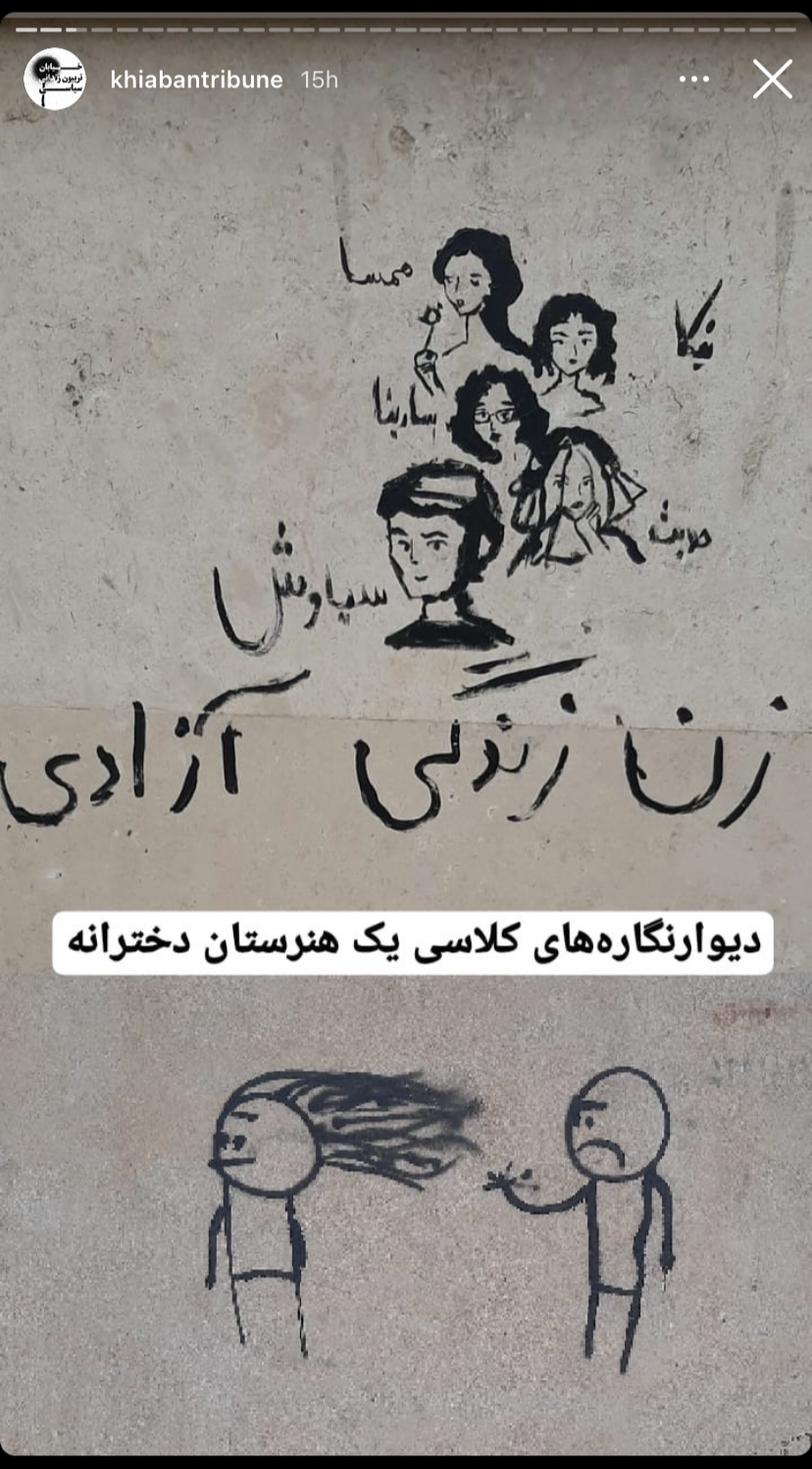

Khé (خ). The story included high school students too, defiantly pulling down the pictures of postrevolutionary Iran’s (clerical) Leaders, Khomeini and Khamenei, which adorn all their classrooms, and replacing them with the words Zan, Zendegi, Azadi, or the names of other girls killed in the protests—names like Nika Shakarami, Sarina Esmailzadeh, both 16. Videos circulated of middle school girls in Karaj ousting a Ministry of Education official sent to dole out disciplinary punishments from their school. Reclaiming their space, they echoed the university students who said: “This—school—is our home. We’re not going anywhere.”

Figure 10. Instagram story by @khiabantribune of wall-drawings in an all-girls art high school of Mahsa (Amini, died age 22), Nika (Shakarami, 16), Sarina (Esmailzadeh, 16), Hadis (Najafi, 22), and Siavash (Mahmoudi, 16).

Daal (د). The story played out on the streets and lived in our phones, desires and hopes and fears whispered across multiple inboxes: “When the schools let out after noon, elementary school girls take off their maghna’es* and hold them in their hands and chant zan zendegi azadi, I see them and I die for them but Sareh I’m scared for them I don’t know what they might do to them.” What we did know was that “they”—the state—lost its ability to silence women with its cruelty. Young girls proved that like fear, courage is contagious too.

*A requirement of girls’ school uniforms, this cloth is a circular,

triangularly cut headscarf that covers the hair and neck.

Figure 11. Screenshot of Instagram dm sent to author by a friend in Tehran.

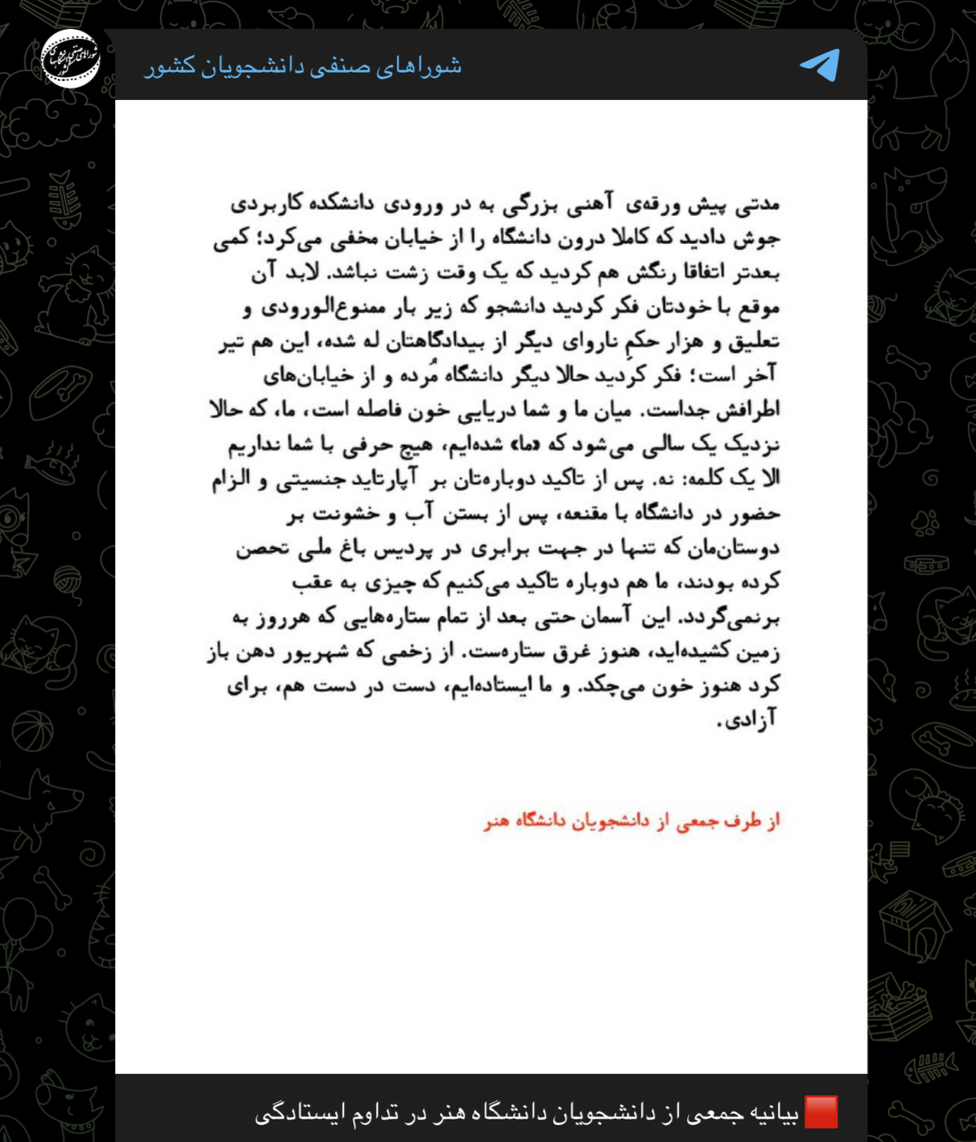

Zaal (ذ). The story circled around and back, when in June 2023, finals approaching, the University of Art tried to impose maghna’es on their students. The students clapped back: “A while ago you welded a large iron sheet to the entrance of the Applied College which completely hid the University from the street; […] you thought that the University is now dead and separated from the streets surrounding it. […] It’s been almost a year since we have become a “we,” we have nothing to say to you except one word: No. […] And we stand, hand-in-hand, for freedom.”

Figure 12. Screenshot of “manifesto of a student collective at the Art University” shared on the “Union Councils of University Students Nationwide” Telegram channel, June 2023.

Ré (ر). The story is that after they refused to oblige the newly announced set of old rules, other students at other universities around Iran came to their defense. “No” was their common refrain, along with: “Nothing will go back to the way it was.” They refused to cede back their campuses, their streets. And so it shouldn’t have come as a surprise when young women took to the streets with chains in July 2024. But they did this thing and the thing they did went viral, and the authorities called them in for a different set of questions.

2. Zanjeer.

Zé (ز). The story starts offline, but it doesn’t become a story until it’s digitally captured and spread, after Jina (Mahsa) Amini was killed and women, young and old, interconnected to amplify each other’s demands. Zé is for zan (woman), zé is for zanjeer (chain). At least as far back as 2015, when a camera captured them together.

Figure 15. Blogged image of a young woman participating in the mourning ritual of zanjeer-zani, 26 October 2015.

Zhé (ژ). The story builds on itself, bringing more questions to light: What is a chain? What are chains? Definitionally, a chain is a “connected series of links of metal or other material,” its earliest etymology associated with the twelfth-century Old French term, chaeine. Circa 1600, the noun gets associated with its other use, “that which binds or confines.” But since 2022 and in Iran, what’s been pushed to the surface of visibility is the chain as it performs its connective function: to twist, to twine, to weave around one another, organize and fortify strength.

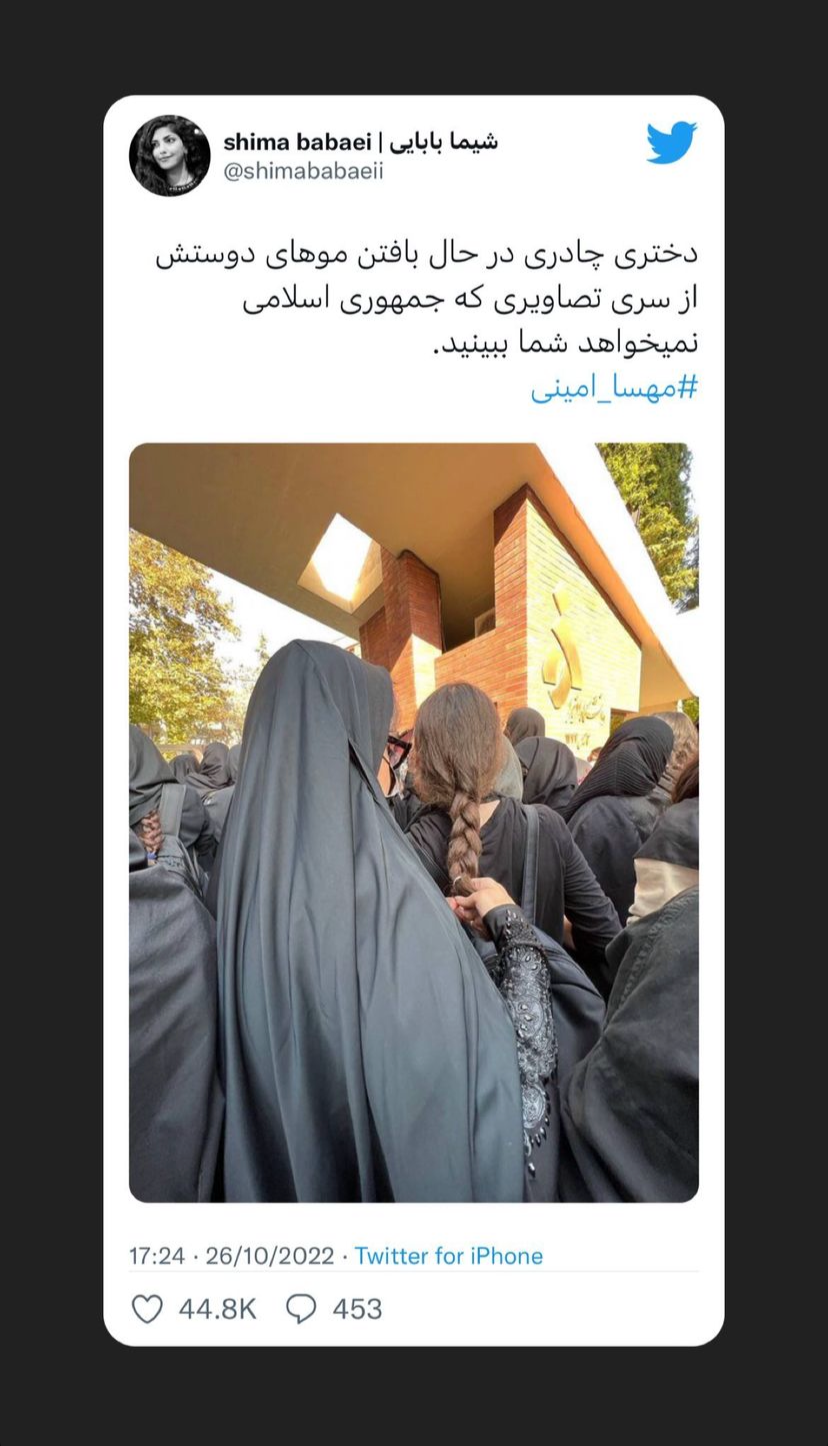

Figure 16. Screenshot of image of a student braiding the hair of another outside of Alzahra University, a women’s university in Tehran, shared on then-Twitter, now-X, by Shima Babaei, an exiled Iranian activist who left following imprisonment for participating in the “Girls of Enghelab Street” movement’s civil disobedience protests (2017–19).

Seen (س). The story that unfolded on the streets was that of secrets, told. What Jina’s Revolution visually revealed, was that many women would doubtlessly dress differently, given the option. That they wanted the freedom to choose, and the freedom to respect and support one another’s right to choose, regardless of whether and how their choices spoke to their religious leanings. On the streets, young women substituted chains of confinement with those visualizing their interconnectedness, dancing around as they used to, as children, when they sang a different song: “Amou Zanjeer-Baf” (“Uncle Chain-Weaver”).

Figure 17. Viral image of women and girls twirling around a bonfire in late September 2022, Bandar Abbas, Iran.

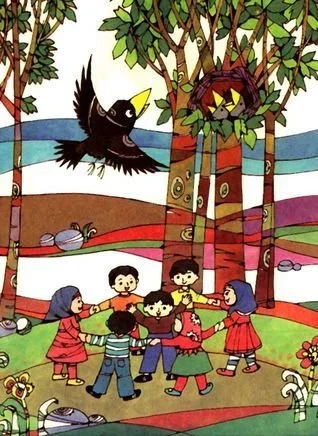

Sheen (ش). The story is of childhood memories of holding tight. Holding hands to form a chain, twirling around one child in the center, singing: amou zanjeer-baf / baleh (yes) / zanjeer-e mano bafti (did you weave my chain?) / baleh / posht-e kooh andakhti? (did you throw it behind the mountain?) / baleh / baba oomadeh (papa’s arrived) / chi chi avordeh? (what’s he brought?) / nokhodchi kishmish (chickpeas and raisins) / bokhor o biya (eat it and come) / ba seda-ye chi? (with the sound of what?) / ba seda-ye gorbeh (with cat sounds) / meow meow meow.

Figure 18. Cover of Amou Zanjeer-Baf by Asadollah Shabani.

Saad (ص). The story, if I remember it right, goes like this: after the children start sounding out animal onomatopoeia, the child at the center tries to spot the weakest bond, to break up the chain, exerting force against the outstretched arms until eventually, one gives in. They swap places, one getting to partake in the pleasure of holding hands, the other, forced to occupy the center, alone. While the game is named after the central figure, the enviable position is that of the periphery. And where is power?

Figure 19. Screenshot of Instagram post by a friend in Tehran of a WLF rally held outside Brooklyn Public Library.

Zaad (ض). The story of power is, as always, as power itself, everywhere. And in the relativity of it all, perhaps the primary question isn’t where power resides, or even how to usurp it, topple it. Maybe the question is how to increase our collective power more so than how to lessen the power of the state. Maybe the answer is to make state power feel encircled, left out, that which doesn’t belong—condemned by the people to the center.

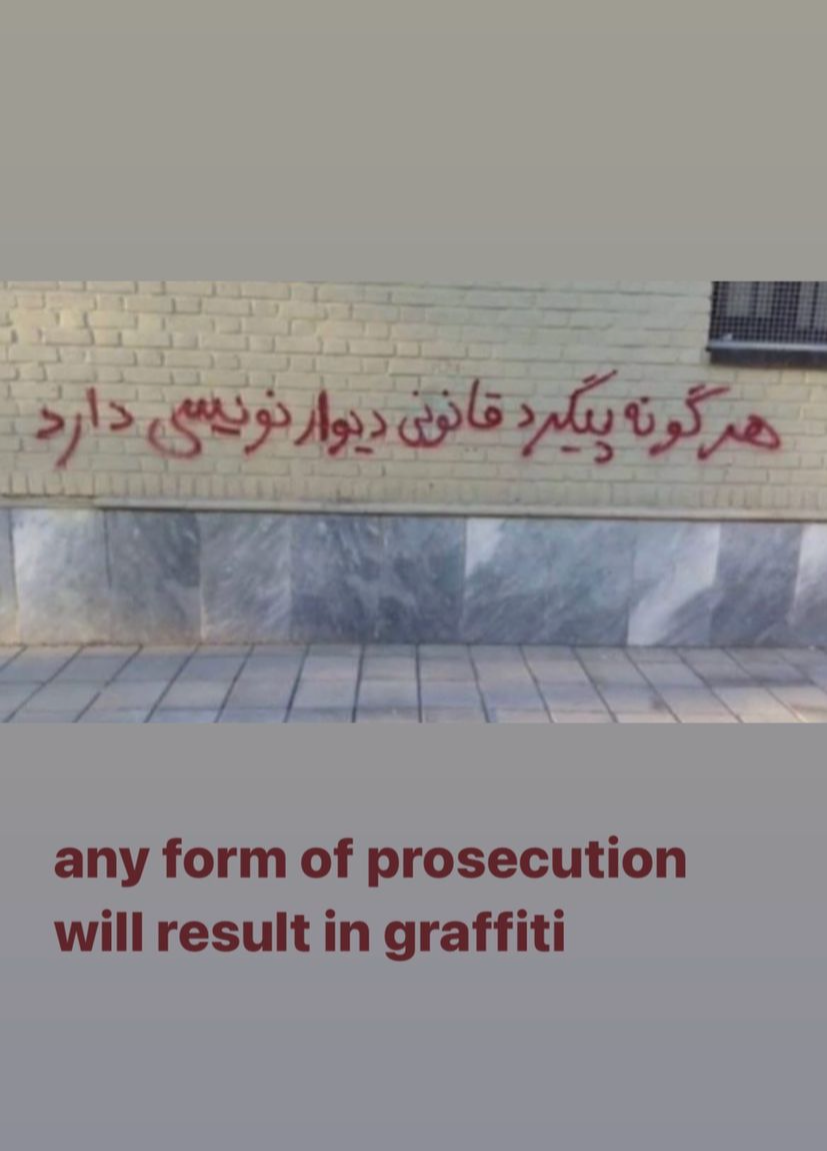

Figure 20. A poster design by a Tehran-based artist on display at Pratt Institute’s “Vigil for Iran” event, 3 October 2022.

Taa (ط). The story of power, conventionally told, locates it at the center. Told otherwise, the center is determined by where power systemically, historically resides. But power also surrounds: conjuring the ghost of their childhood game, young women in Iran showed how it resides in the hands holding tight, the human chains we form together, around it. And it crowds us in too. Power is everywhere.

Figure 21. Instagram post by author captioned: “poetic manifestation of emma goldman’s “if i can’t dance, i don’t want to be part of your revolution,” and my heart that dances & breaks. / woman, life, freedom: in awe of the women of #iran, burning their scarves, shearing their heads, facing down a brutal, bloodthirsty patriarchy & (always) leading the way to nationwide transformation by embodying it first ♥️ / clips from sari (1) & kerman (2), 9.20.22.”

Zaa (ظ). The story, in 1953 Iran, was also of power, playing out between the state and protesting college students killed on campus. Poet Ahmad Shamlou beseeched the “Fairies” (“Pariya”) to stop crying, to collect as a people instead: age ta zood-e boland shin (if you get up while it’s early enough) / savaar-e asb-e man shin (and get on my horse) / miresim be shahr-e mardom, bebinin: sedash miyad (we’ll get to the people’s city, see: you can hear it) / jing o jing-e rikhtan-e zanjeer-e bardehash miyad (you can hear the jing-jing of chains breaking off the enslaved).

Ein (ع). The story continues: Shamlou tells the fairies that the enslaved are ready to pick up torches, to set them on the night, to destruct darkness. To throw a saddle on Amou Zanjeer-Baf and push him to the middle, not to cheer but to belittle him, his position. To “hold each other’s hands tight / dance around the dude / playing [a different children’s game] ‘the bath has ants, sit and stand.’” Shamlou said he was so lost in the innocent un-knowing of childhood that he thought this revenge enough. Is changing the game a better challenge to power?

Figure 23. Image from an Instagram carousel inviting protestors to partake in a nationwide general strike as the primary form of “collective power” against the state.

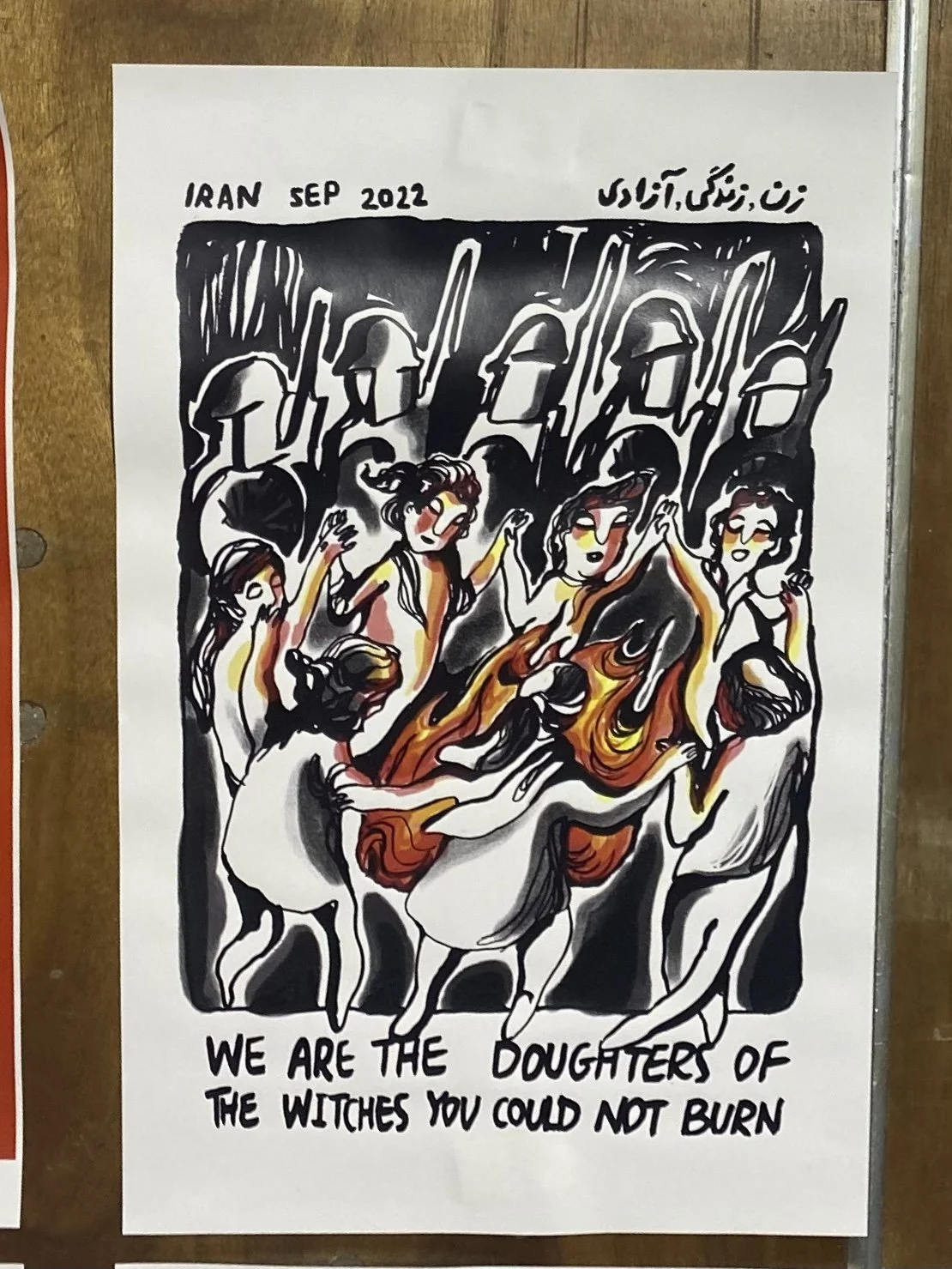

Ghein (غ). The story we all know is that we can’t dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools. But can we, by reimagining the tools, use them in practice to build other houses, away from all that? What is a chain? Zanjeer is comprised of zeen (weapon) and jeer (gear): a chain, no matter how you look at it, is a way of getting caught up. Caught up in what, might just be the answer. As for the story, it bears repeating. The question is, when do you hit start? “Any legal prosecution will be met with wall-writing,” they wrote.

Figure 24. Screenshot of friend’s Instagram story of the transformative wall-writings that were changing the surfaces of cities across Iran, making it impossible to deny the revolution afoot. When the government threatened legal prosecution of anyone caught doing graffiti, the people responded in kind.

3. Zanjeer-Zan.

Figure 25. Screenshot of friend’s Instagram story featuring schoolgirls in Kurdistan braiding each other’s hair in front of a class whiteboard with “Long Live Kordestan” and “Jin-Jiyan-Azadî” written on it.

Fé (ف). The story starts offline, but it doesn’t become a story until it’s digitally captured and spread, after Jina (Mahsa) Amini was killed and women, young and old, interconnected to amplify each other’s demands, got caught up in each other’s courage. They told their stories from their city walls, schools and classrooms, public bathrooms. On one Tehran sidewalk, they wrote: “this fall the weather isn’t [suited] for two [a couple], it’s for 80 million [Iranians].” Spaces spoke of nothing else: the sayable and unsayable, visible and invisible, were recharted for good.

Figure 26. Screenshots of Instagram/Twitter posts and stories of girls and young women in Iran marking their spaces with signs of protest and sisterhood, in presence and absence alike.

Ghaaf (ق). The story of togetherness unfolded in two ways: natarsid, i.e., don’t be afraid—we are all together. And beterasid, i.e., be afraid—we are all together now. Different propositions for different audiences. With this statement, together they moved through spaces, calming some, frightening others. New divisions between the visible and invisible formed too: unveiled young women stepped away from work to enjoy, in plain view, breakfast at a café in a conservative neighborhood, while their fellow city-dwellers covered Tehran’s metro cameras with sanitary pads to blind the eye of the state in the sky used to track protestors.

Figure 27. Screenshot of Instagram story by author juxtaposing a tweet by Donya Rad, who was arrested in Tehran for sharing this image of herself enjoying breakfast as an uncovered woman, with an image from the 1960s Greensboro civil rights protest sit-ins in the U.S. which also resulted in the arrest of Black students who resisted the segregationist policies that denied them service at lunch counters (Bettmann Archive).

Kaaf (ک). The story is one of experimentation, one of and for performance studies. “What does it do in the world?,” performance studies asks. These girls and women, un/wittingly, answered. They set off (with) a question: What happens if I do this thing? Iran is visibly changed in WLF’s wake. In urban spaces, home to 77 percent of Iranians, many refuse to go back to covering their hair. Having realized their strength in numbers through participation in street protests and social media circuits alike, a tacit agreement was reached between women: they banked on one another’s insistence on bodily autonomy.

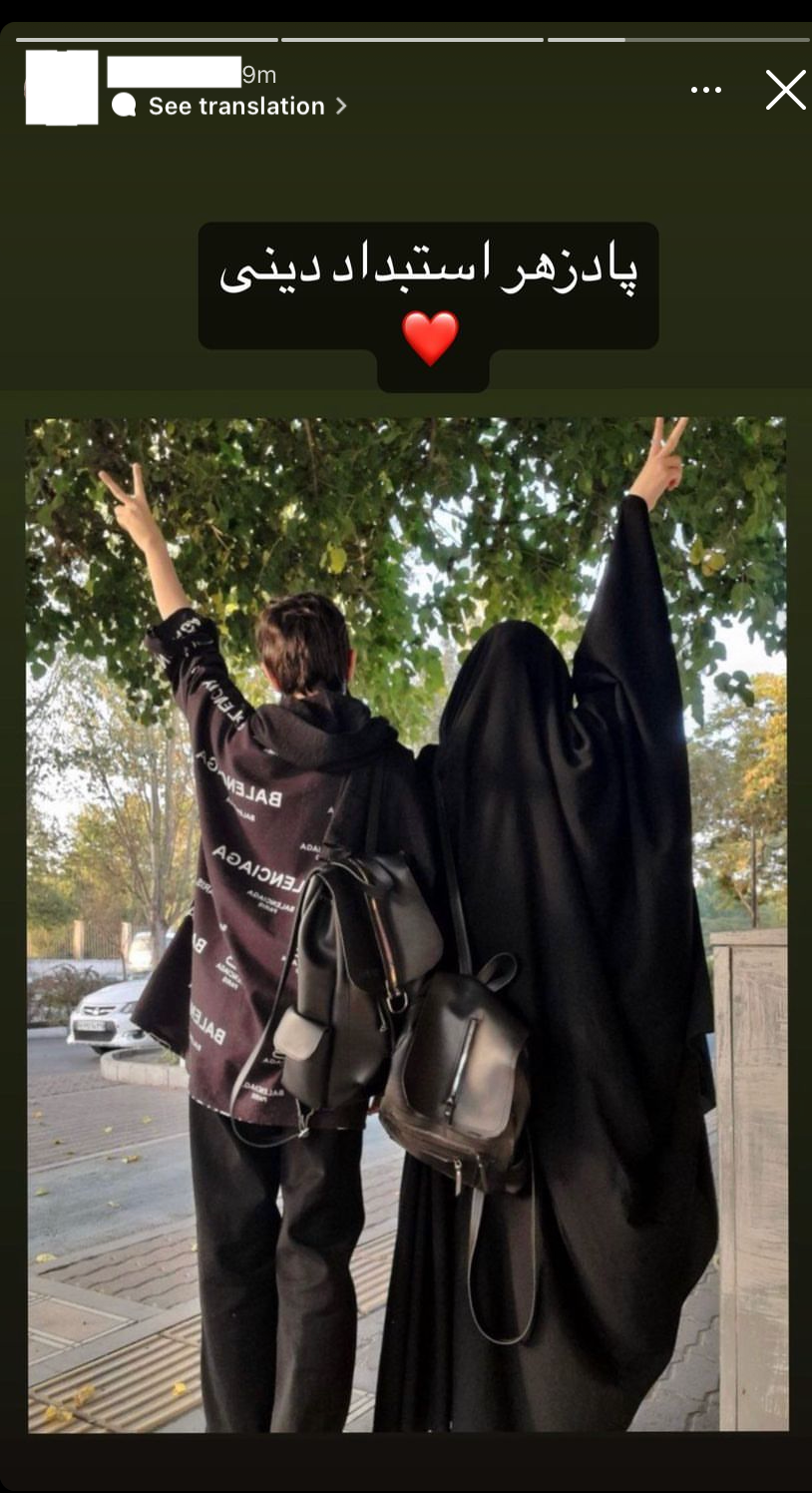

Figure 28. Screenshot of Instagram story by a friend with an image of two young women, one dressed in traditional chador, the other without a headscarf, with the caption “antidote to religious tyranny.”

Gaaf (گ). The story also fomented denial. Some denied the social revolution underway in this very agreement. Which was to deny how women, always already subject to the risk of arrest by the state’s guidance patrol (est. 2005), shifted the parameters of that risk by enacting their will for bodily sovereignty in the very manner they engaged with/in their communities. To deny the ways in which girls and women have continued to experiment with how to keep pushing the limits of public permissibility, the most conspicuous instance of which happened during Ashura, an annual day of ritual street performance in Iran.

Laam (ل). The story is that in deference to the martyrdom of Shiism’s third Imam, Hossein, Iranians partake in collective mourning. While Western academe has attended considerably to the performance form of taʿziyeh, it’s mostly reduced it to a version of the Christian passion play. But Iranians can tell you that taʿziyeh is a performance of mourning encompassing a constellation of dramatic and ritual performances, stationary and mobile elements. The latter, exemplified in the dasteh, involves locals marching through streets, singing and self-flagellating in the form of sineh-zani (beating rhythmically on one’s chest) or zanjeer-zani (rhythmically hitting one’s shoulders with chains).

Mim (م). The story is conventionally manly: among these bands of marchers, those yielding chains—zanjeer-zan—have exclusively been boys and men. Until one year ago, when young, unveiled women joined their ranks, their uncovered hair glistening in the sun, refusing to cede the streets to their male-presenting counterparts. Creating a viral moment, they forced Iranians to grapple with pressing questions explicitly being put to them: Who decides how I/we show up and partake in public religious rituals? Who is the state to restrict the bounds of (my/our) religiosity?

Noon (ن). The story is a contradiction in terms—unveiled women performing religious defiance and religious mourning—that infused religious rituals with a singular dynamism. Read as an instance of becoming both zan and zanjeer-zan, the literal and figurative significance of this event is encapsulated in the act-ual opportunity to reexamine the often-overlooked power of global feminist uprisings, particularly in their emergent sociopolitical, racial, and economic intersections among millennials and gen Z. Irrefutably tech-savvy, they’re demonstrating that they’re not just aware of, but also recognize the importance of embodied street tactics and occupying public spaces as a counter to state terror.

Vaav (و). The story is rendered richer as it merges with taʿziyeh: an expansive, theatrical medium that stages prophets, imams, angels, and even god to (re)tell a spiritual story in the form of an annual enactment of religio-national renewal. Malleable to the core, taʿziyeh has the potential not just to change, but to influence change. More than a site for patriotic dis/identification, taʿziyeh rituals have historically been where the other’s culture(s) and gender(s) were donned, shed. Ta’ziyeh’s message has always been one of revolt against injustice. And form has conveyed this message. And the young women took to it, embodied revolution.

Hé (ه). The story starts with “esteghlal, azadi, jomhoori-ye eslami”: independence, freedom, Islamic republic went the tripart chant heard around Iran during the uprisings that delivered the 1979 revolution. Demonstrably failing to deliver any of these criteria to Iranians, this triangulation was dis/replaced by “zan, zendegi, azadi.” A call to womanhood, to shifting the seat of power by redefining power altogether. To life, countering all the death that’s been glorified culturally in the state’s nation-building project. And to freedom, redefined by a generation of young women in their willingness to set fear on fire, declaring fear inherently antithetical to their freedom.

Yé (ی). The story starts with “yeki bood, yeki nabood”: one was, one wasn’t. Some have lazily translated this opener to the stock phrase, “once upon a time.” But while they both signal the start of a story, the Persian phraseology acknowledges both the present and the absent: comrades we finally found, comrades we bitterly, violently lost. The story starts with “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî,” travels along as “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi,” and expands outwards to encompass, as “The Song of Leilas” did, “solh o omid o shadi”: peace and hope and joy.

AKNOWLEDGMENTS

All my gratitude to Beeta Baghoolizadeh and Emily Mitamura for their thoughtful reviews and generous feedback on the fragments above.

SOME THINGS I THOUGHT WITH

Afshar, Sareh. 2010. “Are We Neda? The Iranian Women, the Election, and International Media.” In Media, Power, and Politics in the Digital Age: The 2009 Presidential Election Uprising in Iran, ed. Yahya R. Kamalipour, 235–50. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Afshar, Sareh Z. 2020. “Postrevolutionary Retrojection: Azadeh Akhlaghi Stages 17 Deaths in Iran.” TDR/The Drama Review 64(1): 36–61.

Afshar, Sareh Z. 2025. “Necrogeographies: War, Mourning, and the Aesthetics of Allegory in Gohar Dashti's Photographs.” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies (September): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2025.2529218

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ansary Pettys, Rebecaa. 1981 “The Taʿzieh: Ritual Enactment of Persian Renewal.” Theatre Journal 33, 3 (October): 341–54.

Bajoghli, Narges. 2024. Sanctioned Lives. SP Comics. www.webtoons.com/en/canvas/sanctioned-lives/sanctioned-lives/viewer?title_no=938100&episode_no=1

Berlant, Lauren, and Kathleen Stewart. 2019. The Hundreds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chelkowski, Peter J. 1975. Taʻziyeh: Indigenous Avant-Garde Theatre of Iran. Tehran, Iran: Festival of Arts Series.

Dabashi, Hamid. 2010. “Ta’ziyeh as Theatre of Protest.” In Eternal Performance: Ta’ziyeh and Other Shiite Rituals, ed. Peter J. Chelkowski, 178–91. London: Seagull Books.

Hammad, Isabella. 2024. Recognizing the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative. New York, NY: Black Cat.

Lefebvre, Henri. (1992) 2004. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time, and Everyday Life. London, UK: Continuum.

Marzolph, Ulrich. 2009. “Storytelling as a Constituent of Popular Culture: Folk Narrative Research in Contemporary Iran.” In Conceptualizing Iranian Anthropology: Past and Present Perspectives, ed. Shahrnaz R. Najdmabadi, 30–42. New York: Berghahn Books.

Mottahedeh, Negar. 2010. “Karbala Drag Kings and Queens.” In Eternal Performance: Ta’ziyeh and Other Shiite Rituals, ed. Peter J. Chelkowski, 149–69. New York: Seagull Books.

Mottahedeh, Negar. 2023. “Anti-Disciplinarity and Solidarity with ‘Woman, Life, Freedom.’” In Feminist Futures, edited by Narges Bajoghli and Sareh Afshar. www.feministfutures.org/feminist-futures/anti-disciplinarity-solidarity-women-life-freedom-negar-mottahedeh.

Osanloo, Arzoo. 2023. “Challenging Benevolence: What’s Revolutionary about Iranian Women’s Uprisings?” In Feminist Futures, edited by Narges Bajoghli and Sareh Afshar. www.feministfutures.org/feminist-futures/challenging-benevolence-iranian-womens-uprisings-arzoo-osanloo.

Osman, Wazhmah, and Narges Bajoghli. 2024. “Decolonizing Transnational Feminism: Lessons from the Afghan and Iranian Feminist Uprisings of the Twenty-First Century.” JMEWS: Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies20(1): 1–22.

Taylor, Diana. 2003. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Thiong’o, Ngũgĩ wa. 1997. “Enactments of Power: The Politics of Performance Space.” TDR 41, 3 (Autumn): 11–30.

Ybarra, Patricia, and Marlon Jiménez Oviedo. 2023. “El Violador Eres Tú: Interrupting State Performances of Patriarchy.’” In Feminist Futures, edited by Narges Bajoghli and Sareh Afshar. www.feministfutures.org/feminist-futures/el-violador-eres-tu-interrupting-patriarchy-patricia-ybarra.

CITATION

Afshar, Sareh Z. 2025. “When Zan Became Zanjeer-Zan: Jina’s Revolution, Retold.” In Feminist Futures, edited by Narges Bajoghli and Sareh Afshar, 29 September, https://www.feministfutures.org/feminist-futures/when-zan-became-zanjeer-zan.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SAREH AFSHAR is a writer, translator, storyteller, and co-founding editor of Feminist Futures. Committed to scholarship on movements for change and their artistic and digital footprints, their writing has appeared in Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, TDR/The Drama Review, e-misférica, Text & Performance Quarterly, Khayyam, Ravagh, and edited book volumes. Having earned her PhD in performance studies from NYU, her work has been awarded generous support from interdisciplinary centers, including Brown University’s Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women, where she was a Postdoctoral Fellow in Gender Studies, and Princeton University’s Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Iran and Persian Gulf Studies, where she is currently Associate Research Scholar.